Over the last nine years, I have collaborated with around 500 kids K-5, usually twenty at a time, to write over a dozen songs about character education, science and local history. This project has been so rewarding for my soul! I’m putting this article together to outline my process, since I think it’s transferable, and so that more kids and communities can benefit from this fun process.

Over the last nine years, I have collaborated with around 500 kids K-5, usually twenty at a time, to write over a dozen songs about character education, science and local history. This project has been so rewarding for my soul! I’m putting this article together to outline my process, since I think it’s transferable, and so that more kids and communities can benefit from this fun process.

If you are a music teacher, classroom teacher, principal, administrator, composer, songwriter, musician or an interested parent, I would be happy to discuss any of these ideas in greater detail to figure out how to customize a program that you can bring this process to your local school, or organization.

Two quick things to note: I’ll admit that I don’t necessarily think that my process is particularly original – I expect there are others that are doing similar, worthy projects. I’m sharing what works for me, and pointing out some areas that I think are important. Also, all the benefits that I point to are anecdotal, taken from classroom teachers, music teachers and my observations.

Benefits – Why write songs with kids?

Music, plus a whole lot more In my workshops, I teach more than just musical ideas. I cover basic songwriting, general music concepts, the principles of narrative, how to construct a story, learning about working collaboratively and the creative process. Depending on the topic I have also included discussions on character education, community activism, science and history; where those last two are linked to the Common Core and to the State of California Standards. Yes, it sounds pretty deep, but many of the songs are pretty funny! (Listen to “The Plankton Song”)

Songwriting is empowering There is a wealth of great music written for kids to perform, however when kids are part of the songwriting process, and they get the opportunity to perform material they helped create, they demonstrate a huge sense of pride from literally having their ideas heard. The schools where I have written songs have a special new identity for these creations, even years later – “these are our songs”. (Watch “Kinder Than Necessary”)

Kids work closely with their topic When we write songs together, the students work with the subject matter in a number of ways. It keeps the topic fresh while they take a deep dive into their topic. They first learn about subject matter with their teacher in the classroom, then I discuss the subject matter with the kids during the songwriting process, and together we uncover then the essential elements of the subject matter – these become a main ingredient to the song. Next, they learn the song, which is a repetition of those essential elements, often memorize the song i.e. the main theme and supporting facts of the subject matter. Then they perform the songs, often for other students, and they have the opportunity to teach other kids about what they’ve learned. (Listen to “Symbiotically” from We Are Coral)

Kids teach kids There are a few points in this project where kids teach other kids, which I find to be amazing. During the lyric writing process, the kids discuss what ideas and elements are the most important for the song. They often recite facts that their teacher has taught them. Kids remember different bits and pieces, and they piece them together to make a whole story, which in turn becomes a song. Poetic, right?

The next kid-teach-kid learning opportunity happens when the kids perform their songs for other grades, younger and older. Most often the younger kids are hearing these ideas for the first time, and the older kids are getting a review or a slightly new take on ideas they’ve learned in previous grades.

Kids have different styles of learning There are always a few kids that are surprise thrivers during my workshops. These are kids that the classroom teachers report as being bored sometimes, or a little hard to reach. Music and songwriting unlocks something in these kids. Somehow, a change comes over some children during the songwriting process. In some cases, the kids might be shy and not overly comfortable with sharing their ideas in class, but somehow music affects them on a different level, and they begin to open up. The power of music should not be under estimated!

The Recipe

I have honed my process over a nine year period, with the help and input of some great classroom teachers, a fantastic music teacher, and some open minded kids. I have written character education songs with 1st graders, a nine song coral reef musical with 2nd graders, a local history review with 3rd graders and a song about kindness with a huge collaboration of an entire K-5 elementary school.

In all of the projects I’ve worked on, the common factor is that kids have generated all the ideas for the lyrics. I flip some words around, put them in an order, and help them figure out the main idea, which becomes the chorus. But when I say the kids write the lyrics to these projects, I really mean that they write the lyrics – to me, that is the secret sauce. That part is non-negotiable. I try my best to include as many ideas as possible and to leave whole phrases intact, so they are recognizable when the kids experience the songs.

Here’s my basic recipe. I realize this is a lot to pull together, and I’m grateful that I’ve been able to sustain this for so many years. Ingredients for writing songs with kids:

1 Engaged classroom teacher – willing to spend the necessary time to see the project through, including to help the kids learn the songs

1 Topic to write about (anything could work, examples are character education, science, history)

1 Chunk of time, agreed upon by the classroom teacher and the music teacher

1 Small funding source to pay for the program

1 Engaged person to write a grant (optional)

1 Supportive administrator like a principal

1 Group of kids – Generally one classroom/group of kids works well to write one song

1 Open-minded songwriter – ability or access to record and deliver drafts and completed songs

1 Dedicated music teacher – willing to teach the songs, sometimes in lieu of learning other songs, or sometimes during classroom time

1 Confirmed performance

The Process

I generally like to meet with the kids a few times – once to introduce songwriting, once to gather ideas to write, once to introduce the song. I have been able to keep my classroom times pretty low, partly to keep the grant amounts reasonable.

For my first session, I like to present an introduction to songwriting and songwriting form so the kids get used to me, and we can get used to working together. During this process, I often try to quickly generate some ideas to begin to write a song on the spot. I make an effort here to show them that creativity can be fun and casual – all we need is a little bit of structure. (During this first session process, this song came together with 1st graders. It was a week before MLK day. We talked about Dr. King for a few minutes, then I asked them about their dreams. (Listen to “I Have A Dream”)

At some point before my next meeting with the kids, I like for the kids to have learned something from their teacher – if it’s history or science-based, they may do some research. If it’s character education, they may read an age-appropriate book.

Often during this classroom learning the teacher takes notes that they bring to this session, so the kids can see. These can be helpful for the kids to review, especially if the learning has been more than two weeks before. What I’m really looking for is for the kids to convey ideas in their own words. While it can be hard sometimes, we always get there!

I’m always glad for the classroom teacher to be present during this session, and if they have any specific notes or directions that the song should take, I always ask for their input. However, it’s crucial that teachers and other adults present participate as little as possible with the idea gathering, other than help with aspects like calling on students. Words from adults can sometimes be more eloquent than necessary – I honestly think it’s the words from the kids that give these songs their magic. (Listen to “Honesty”)

When I meet with the kids for the second session, we quickly review songwriting form then move forward to work on lyrics. To them, I make it clear that we’re just working on ideas. I try to start with a blank canvas. I also try to just listen and get them to talk, asking questions to learn more about what they know. I sometimes remind them that we’re just looking for ideas, not necessarily perfect lyrics or phrases. I find that if kids, especially in the younger grades try to give what they expect means a clever idea, it often comes out a bit forced. We don’t worry about rhyming, order or anything that might get in the way of their free thought.

Toward the end of this session, I try to make sure we agree as a group about a working main idea, that could work as a chorus. I like to try to demonstrate some music ideas that might work on the spot to allow the kids to have some input on what genre(s) might work for the song. I also try to show demonstrate some ideas that probably wouldn’t work well, maybe playing music against the subject matter (like a sad music for happy lyrics).

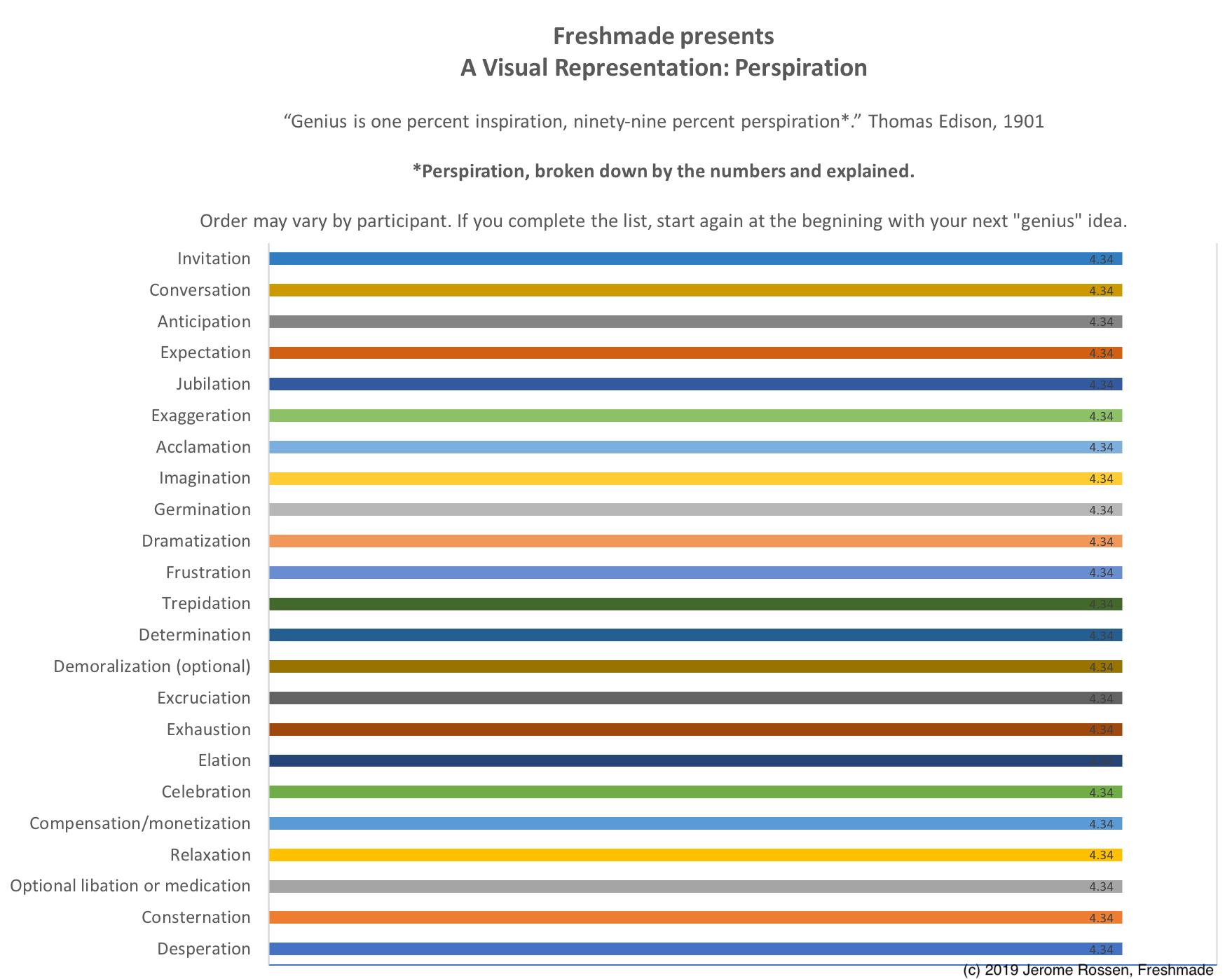

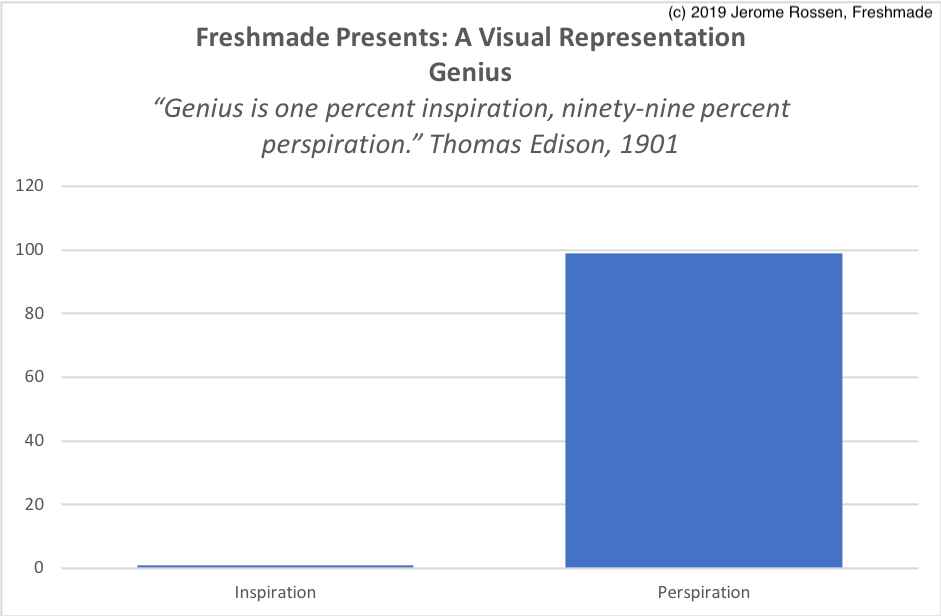

Next, I take the ideas into my studio and fashion them into a song. I wish I could better explain how I put lyrics into music! I realize this part of the process is pretty important but I just don’t know how to break it down to explain it… I supposed it’s like trying to describe to someone how to walk – you put one foot in front of the other, and place your weight on your front leg when you do it… but that doesn’t quite describe walking. I’m certain that each musician and songwriter would have their own process here. I suppose that the right songwriter is a rather crucial ingredient for this process to work.

I like to make the songs singable and memorable for the kids, and I try to make sure the kids can sing them, making sure that it’s in their range. In my approach, I write songs that are written and performed by kids – but I don’t write “kid songs” per se (not that there’s anything wrong with those). I have found that kids can handle pretty sophisticated syncopation and harmonic motion. I generally use Pop songs and classic Broadway songs as a reference.

I generally continue to work on the chorus first, but not always. I really try to get all the kids ideas into the song with the aim of keeping the song at around three minutes or less. Once I feel like the song has the right flow, I make a scratch recording and share it with the music teacher for a quick review. Sometimes I make a few tweaks after this process, then I make a better recording, including the piano accompaniment that the classroom teachers can use to teach the song. I will also share the draft lyrics with the classroom teacher to make sure we have all our facts straight, and change anything necessary.

In my third session with the kids, I introduce the song to them. This is generally my favorite part, as they can see the whole process come together. I find it to be really rewarding when they spot their own idea, or their friend’s “you wrote that part!” Once I see whether I need any further tweaks, I create a written music chart for the song so the music teacher can teach it, and so the school can perform it in the future.

At this point, the music teacher and classroom teachers take over the project, teaching the song to the kids. It’s always hard to find time for the kids to learn the song(s), so I find it helpful to at least get a rough idea of when the learning will take place at the beginning of the process so that the teachers can support each other.

Finally the kids perform their precious songs for their parents, and hopefully other kids.

While this process is slightly different every time, it is always rewarding for me to watch the kids collaborate, learn and perform. Do you have questions about how you might incorporate this process into your school or organization? Please let me know if you’d like to learn more about my experiences and to see if together, we can customize a program that works for you.

Jerome Rossen is a composer, songwriter, producer and professional musician. Jerome has worked with over 500 kids to write 15+ songs and counting, including “We Are Coral” a musical about saving the Coral Reef. Jerome creates music for advertising, apps, kid’s video games and TV. Jerome has created music for Originator Kids “Math Tango: Starbase”, Leapfrog and Spinmaster. Jerome has placed his music in major TV shows “The Bachelor” on ABC and MTV’s “The Challenge”. He runs Freshmade Music, an independent audio studio.