I’m an independent composer and songwriter. I focus on kids projects, for TV and the internet.

When the pandemic hit the US, it seemed apparent that the typical projects I work on would be placed on hold, and after a few weeks it turned out I was right. I was unsure where to turn for networking and new business opportunities. After a few months of new normal, I wearily signed up for my first virtual conference, not really sure what to expect. As a natural skeptic, it was easy to for me to make a list of the what I thought wouldn’t go well. Here’s what was going through my mind-

The downsides seemed obvious:

- I wouldn’t be with actual humans (though of course that’s the point), where you meet, have small talk, read body language.

- No chance for randomness. Sometimes the greatest parts of conferences are the random meetings, or casual conversations. Or running into folks I’ve met before, where then introduce me to someone new. In person, this all happens very organically. In a virtual world there would be no framework for this type of serendipity.

To be fair, I was hopeful that it would be time well spent. The plus sides seemed pretty clear:

- Cost – travel, food and lodging = $0. (Of course it’s not lost on me that all the folks in the travel and related industries rely on folks like me to travel for their income. Reason #27 why I can’t wait to travel again.)

- Time – no commute or travel time. I could hang out with my family while I wasn’t virtually attending the conference. I could also continue my regular work, which is kind of nice.

The parts I wasn’t sure about:

- I didn’t know whether there would be a typical exchange of ideas or learning.

- I didn’t know whether it would feel like an escape from my usual routine.

I attended that initial conference and it exceeded my expectations! I had some great one-on-one conversations and saw different insights into creative process, and I got to learn about some really fun IPs that have a lot of potential. This first conference went so well for me, that I signed up for two additional conferences with slightly different formats.

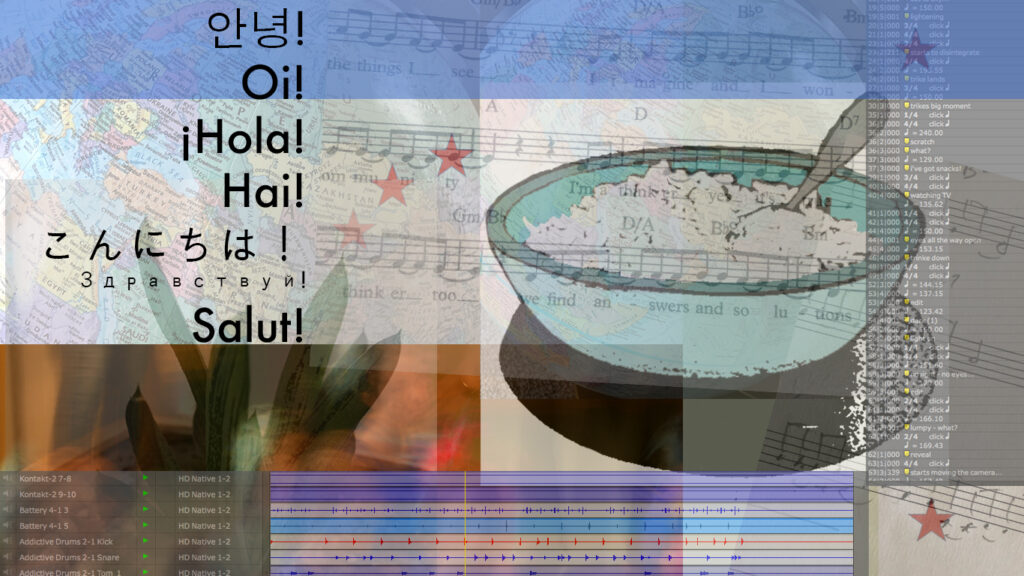

Over the course of 2020, I stayed home and I met with people from twelve different countries. I watched 15 kid’s animation pitches for new shows, and witnessed some great feedback by industry veterans. I screened a bunch of new cartoons that are currently being broadcast in regions around the world. I was inspired by so much amazing content.

Things I’m grateful for:

- I got to meet people from all over the world in creative industries that were really nice.

- In this dark time, folks who were strangers at the beginning of my zoom call were genuinely concerned about the health and welfare of my family.

- I got to meet with inspiring, seriously creative, funny people from all over the world with seriously creative, funny ideas.

- I got to learn about projects and meet people who share values that translate all over the world, like this one: Educating kids through diverse, creative content, with stories that come from a diversity of voices is necessary and possible in so many creative ways.

No, 2020 hasn’t gone the way any of us had planned, and I fear that 2021 could get off to a rocky start. But I’m so glad that I was able to make the most of it, and to “travel” by meeting so many folks, with interesting voices and perspective from all over the world.

When we journey forward into the new normal, I look forward to a hybrid world that will include travel both IRL and virtual. I hope that by including virtual travel to conferences in the future, we will see that there are at least a few positive experiences that we can bring out of this unfortunate time. I look forward to seeing you, or “seeing” you in 2021!