The title music producer is used for many different roles in the music industry. I’ve worked awhile as a composer and songwriter, and I’ve met a lot of people who introduce themselves as a music producer, though to be honest I’m not always sure what they do! A music supervisor is another title that is generally a little more straight forward, but might not always be that clear to everyone. While I can’t speak to what all those other folks do on other projects, I did get the opportunity to function as a music producer and music supervisor on a podcast. So what do I do?

As a music producer and music supervisor, my primary job is to make sure we have the right, great music that matches our exciting, educational and fun story. Also, I’m committed to making sure it is really great-sounding and broadcast quality. In a nutshell, this means leading and owning the efforts of music discovery, music direction, casting, (a little) composing, mixing, editing, and revising. I’ll break down each of these activities a bit further down in this article.

Keyshawn the Keymaker is a fictional podcast for kids that takes place in modern-day Minneapolis. Keyshawn is an 8-year-old on a quest to help someone in his community. In each episode adventure, listeners discover new types of careers and learn key career values. You can listen to it here, (as well as the rest of the fantastic podcasts in the PRX accelerator program I participated in): https://www.prx.org/ready-to-learn.

Here is a break-down of how I approached each these roles:

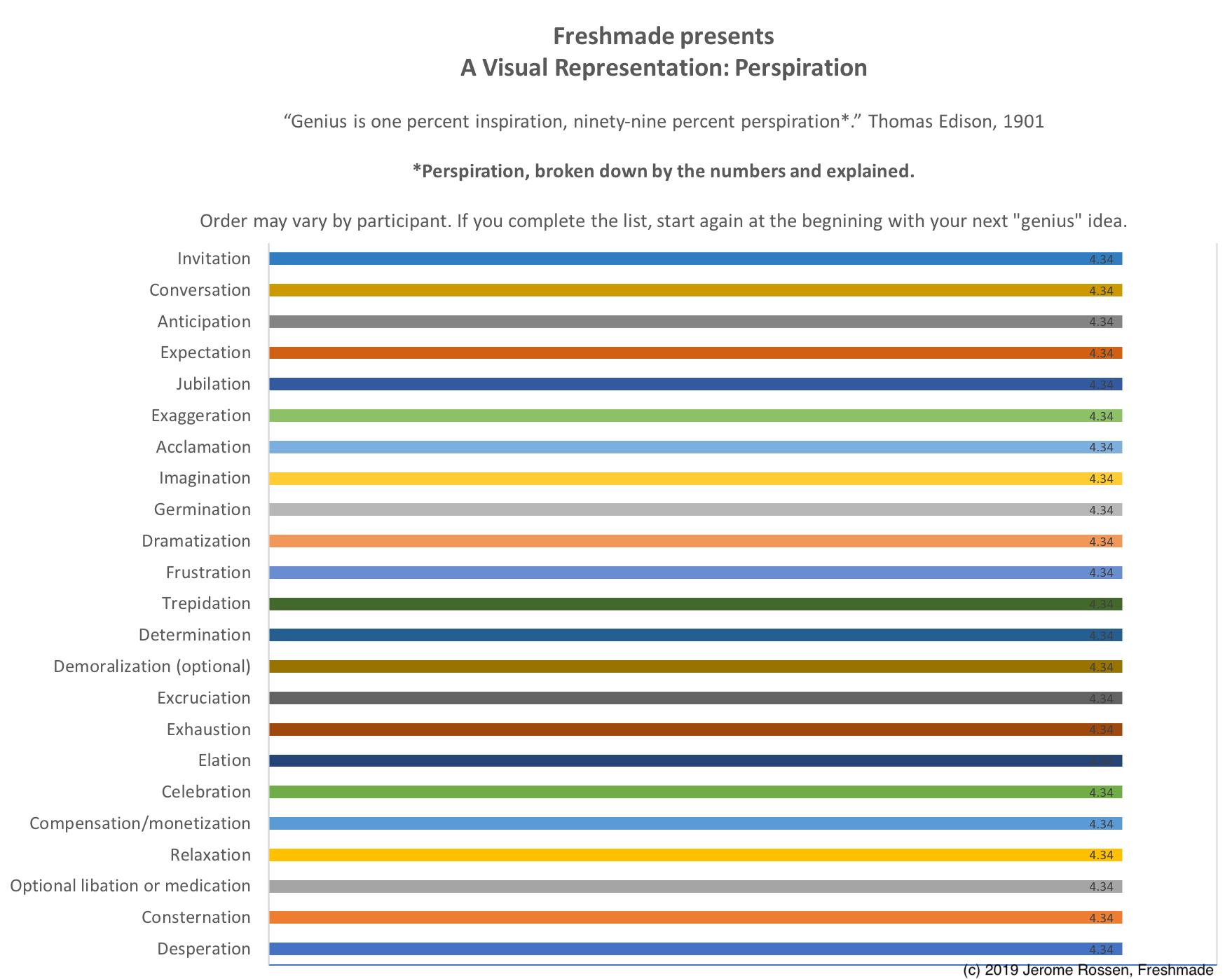

Music discovery and direction Before we could start creating, gathering and listening to tracks, we needed to metaphorically sit down and figure out what we wanted. The process was a bit like building the train tracks at the same time as building the train, since we had to figure out what music we needed, at the same time as we were writing the podcast.

We knew we wanted hip hop music to be the musical heart of the podcast. As we began analyzing different styles of hip hop, we realized we wanted to focus in on traditional, boom bap and more modern, trap. One thing that came up was that many of the beats we listened to for reference felt a little slow for a kids project, so we knew we would need to speed our beats up compared with standard tempos. I also realized pretty early on that this project would need great music for kids, but not necessarily kid’s music — a subtle, but big difference.

By the nature of our development process, I was functionally an embedded regular show producer, not just a music producer (not that there’d be anything wrong with that of course). This meant that I was reviewing scripts and helping guide the direction of our show. We went through a broad process of “I wonder” and “what if”. We kept everything on the table and we tried to create quick prototypes where we could decide what was working. We explored whether we wanted singing, rap, instrumental tracks or other songs. We ultimately decided on instrumental tracks for this pilot. We also made the choice not to include very much background music under the dialog, since we were concerned this would be too stimulating for the younger end of our demographic (4–8 year olds), and we really wanted to make sure that they were able to focus on the story.

The best way for us to streamline the process of finding the right music was to create a playlist of reference tracks, based on music that already exists. As we were trying create a playlist of music we thought would work, sometimes we found it helpful to note what music we thought definitely wouldn’t work, so parts of playlist came together by exclusion.

Music direction and supervision When we selected our beat maker, it was my job to create a written brief to figure out the music we needed in each spot. This activity is similar to when a composer has a spotting session with a director in a film. In this case, I created a document where I could confirm our music needs with the creative team and communicate those music needs to the beatmaker. I found myself referring back to this as we started selecting tracks. Once we generally had an idea of what we wanted, it was time to find a beat creator.

Casting Once we had our definition of what music we wanted, it was time to find the right band, musician, songwriter, composer, or in our case beatmaker. We chose one person to create the intro and transition beats. I could imagine using more than one person on a project this size, especially if there are multiple episodes and certainly multiple seasons.

From the outset, we were determined to find a beat creator from Minneapolis who shared the lived experiences with fictional Keyshawn. After a few starts and stops, we were introduced to Devron Mitchell, who grew up in Minneapolis, and currently lives in sunny Georgia. Devron was able to provide us with a small, original collection of music choices that I picked through, edited and mixed.

Composing I did contribute a little bit of composing in this project, adding sound elements to our intro, since we wanted some sound design from our key machine to be included rhythmically in our intro music. I built a musical sound design layer on top of a customized track that our beat maker created.

Mixing I used our reference tracks here, to help us define our overall sound. It’s important to pay attention to what you like about a track — sometimes just the sound of a reference track, the mix, is a crucial part of what is making the track sound good. Also, it was very helpful to have access to separate tracks, as I found myself muting some of the instruments channels. If you don’t mix the tracks yourself, at a minimum I would recommend making sure you have access to the stems of the tracks you’re working with so you can have maximum flexibility.

Music editing and revisions When we felt like we had the right music, we needed to make sure the tracks interacted with the story naturally; that all the entrances and exits sounded right. Each track needed to be edited for length. We were moving pretty quickly with changes and revisions to the dialog, so I made the music edits. Given some advance planning, some of the music editing could be achieved in pre-production by a composer or beatmaker if you ask for various edit lengths and clean endings.

In summary One of the biggest differences for me in this project compared to my work as a composer, was that I started with a wide, macro lens. When I’ve worked on a project as a composer, someone has usually already identified that I’m likely the right fit for the project. During this macro step, I was able to be more strategic since the planning happened early on, during the development of the project. This process was generally new to me, but it was a step that I enjoyed, and one that I hope to be able to participate in again.

Do you need a music supervisor or music producer? It really depends on how big a role music is playing in your podcast. If you’re feeling confident, and you have access to great music that you can obtain legally, I say go for it — place some music into your podcast and see if you like it! If you’re not sure about your confidence, and you’re on a small team, from what I’ve heard anecdotally, these roles will get filled by default by someone, often the audio engineer. It’s possible this person can do a great job with this. However, if there is a whole lot of work on their plate, as is often the case, it might be good to bring someone in, even for a short period of time to help you with music discovery, help you source what you’re looking for and to help you put a plan together as you move forward. It’s possible that it could save you time in the end, and very likely that it could improve the quality of your podcast.

Care to share? Do you have any experiences that you’d like to share as a music producer or music supervisor? Do you have an experience to share about working with one? Do you have a music producer or music supervisor question about your podcast? I’d love to hear from you!

Jerome Rossen is a composer and songwriter who focuses on kids media for apps, internet, podcasts and TV. Jerome is the music producer for the podcast Keyshawn the Keymaker. He has created a series of ABC songs for preschool kids in South Korea and, music and sound design for the math app Math Tango 2. Jerome creates the music for the Happy Tree Friends, a very funny (though very violent) cartoon for adults and mature kids, with a huge cult following. In addition, Jerome has placed his music in major TV shows like “The Bachelor” on ABC, MTV’s “The Challenge” and USA Network’s “Temptation Island”. He runs Freshmade Music, an independent audio studio.