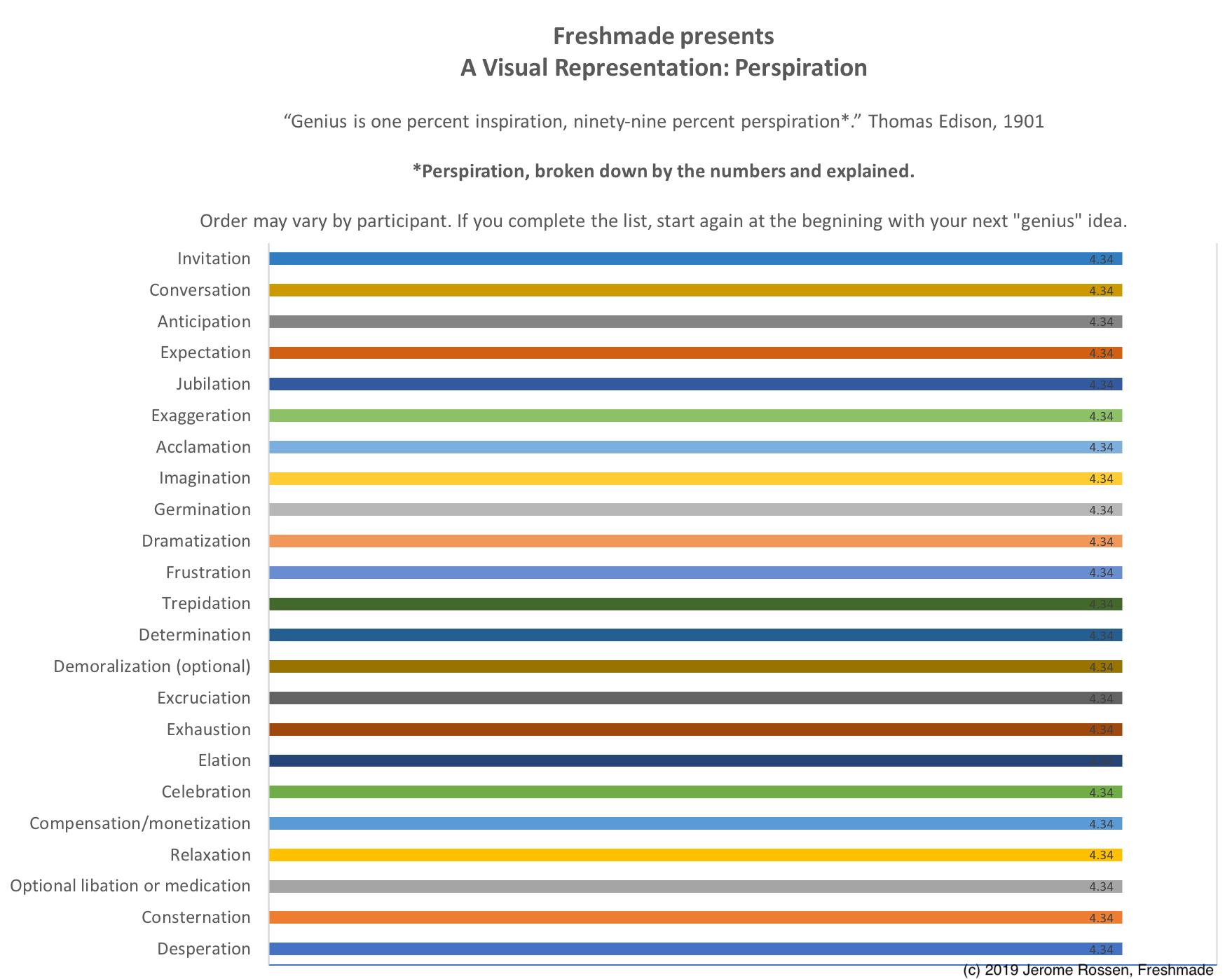

“Genius is one percent inspiration, ninety-nine percent perspiration*.” Thomas Edison, 1901

Work more efficiently with a composer: What is an audio brief, and why do you need one?

An audio brief is a road map, or recipe composers use that contains the logistical, technical, business and creative information necessary to begin creating music for a project. As a composer, I use audio briefs as a way to build consensus to make sure that everyone on the creative team agrees with all the details and the creative direction that the music is heading. The creative folks can be some combination of creator, director, writer, copywriter, producer, art director, or audio director depending on the project and industry. Usually if it’s a large group of people I’m meeting with, they have spoken and agreed on most if not all of these details. I prefer to go through each of these items, even if they seem clear to me, in case any of the details have changed.

Here’s the breakdown of the four parts I like to include in an audio brief:

• Logistical details include deadlines, track length and any required alternate versions. Many of the logistical details will be included in the business contract between the client and the composer, or in a less formal audio agreement. In most cases, I generate the audio brief once the contract or audio agreement is in place, so those details can be brought into the audio brief.

• Technical specifications can be pretty straight forward or complicated, specific to the project. They may include information like the bit rate, sample rate and audio file type, but can also include extensive audio requirements related to finalizing the track before delivery. It can get complicated pretty quickly in a video game project. Many details will be covered in the Game Design Document then incorporated and outlined in an Audio Master Document, which lists out information for all the sound assets in the game, including music, sound design and voice. No matter the complexity, getting these details ironed out early will ensure that the audio files can be easily synced and implemented upon delivery. This is especially helpful toward the end of projects when things are moving fast.

• The business details like the target market, broadcast medium (which may overlap with the technical specs) and any other research that might be helpful to take into consideration when exploring the direction of the music.

• The creative portion generally contains information related to genre, style, and mood. This step in the refining the audio brief usually requires some questions and probing. It There may be references to other audio tracks, or to artwork, which may be completed or in still in draft form. The initial brief I receive may start with something as simple as “upbeat, happy”. After a quick phone meeting with the creative team, I may amend the initial creative portion of the brief to “upbeat, happy – try ukulele, listen to the two reference tracks provided, light percussion but not too heavy, no glockenspiel, not too busy during first part of voice-over”. The second version is a lot more descriptive, right?

Most of my clients generally have a clear sense of what they want. In almost all the cases, they’ve worked on the project much longer than I have and have thought a lot about music options that they think will work. They also have a better understanding about any nuances and context, details that I will learn about if necessary as the project unfolds. My first job is to listen and consider their ideas. My second job is ask questions in order to refine the audio brief, and to make sure I can deliver the best music options possible. I also see it as my obligation to bring my years of experience to offer ideas that I think will work, asking questions like, “Have you thought of this other option?”. Since it can sometimes be difficult to figure out music just from discussing it, it’s often better to hear it. I find it helpful at the beginning of projects to write a few different ideas, a couple of short snippets that we can all examine, then figure out which one is working best and move forward.

During my audio brief meeting, I make sure to confirm all the items including the logistical and technical ones. Since projects often change, I want to make sure I have the latest updates. After I’ve confirmed all of these details over the phone, I will write up my notes into an email and send it to my clients to confirm. Once I get a confirmation from my client and I begin creating and producing music, I can move forward with the knowledge that the whole team is on board.

Creatives, what do you need from the audio brief? If you’re starting from scratch and you haven’t yet hired your composer, sketch out the details that you think your project needs and work with the composer you hire to fill in the remaining details. Also, don’t feel like you have to answer every question you have; in fact I find it can be helpful to know the list of questions or problems that my clients are trying to solve. Also remember, you don’t want to get stuck in process, you want to focus on the deliverable you’re going to receive. I find that it’s less important to my clients how I do my job of composing and producing, then whether I deliver what they’re looking for, when they’re looking for it. If they find it interesting to discuss audio production, I’m happy to explain my workflow and tools.

Composers, what do you need from an audio brief? Everything! If you’re looking through a brief that you didn’t create and anything looks unclear, or if there are acronyms you aren’t familiar with – ask! I would much rather firm up any details related to what my client wants before I start writing music, rather than deliver some music and have them point out something that isn’t consistent with the specs in the audio brief, or deliver something based on a false assumption that I made because I was too shy or embarrassed to ask a question. And as I’ve eluded to above, if the audio brief is incomplete or non-existent, I create it myself.

Audio briefs can be a helpful tool for communication. If used properly, they can be a foundation to a stable creative framework for a project and even to long lasting business relationship. I hope this explanation about audio briefs has been helpful. Do you have any questions? Are there details that you include in your workflow that I’ve missed? Please let me know!

Jerome Rossen is a composer, songwriter, producer and professional musician. For 18 years, Jerome has created music for advertising, apps, and kid’s video games. Jerome has placed his music in major TV shows like “The Bachelor” on ABC, MTV’s “The Challenge” and USA Network’s “Temptation Island”. Jerome also creates the music for the Happy Tree Friends, a very funny (though very violent) cartoon for adults and mature kids, with a huge cult following. He runs Freshmade Music, an independent audio studio. You can learn more at www.freshmademusic.com.

How To Speak Music – 5 Tips For Communicating With A Composer

Pairing music with video is a really exciting process, whether you’re working in animation, advertising, film, television or video games. This step in production usually means that you’re nearing the completion of your project. Perhaps congratulations are in order? Finding the right music for your project is a little tricky, but if you keep a few things in mind and you add a dose of patience, hopefully you’ll get the results you’re looking for.

As a composer and music producer, I interface with a wide variety of folks from a variety of backgrounds who make up my client base. They often have exponentially more experience than I do in art, design, writing and business. They may be a super-talented art director, editor, visionary writer, producer or other type of content creator. No matter what their title is, the job of finding music often falls into the lap of the most creative member or members on the team. In almost every case, everyone on the team has a strong passion for music, and they know from the start exactly what they think will work. Sometimes the hardest part for the team is trying to communicate the musical vision to the person who will be bringing it into fruition. That’s where I come in.

In this article, I am addressing the process of working with a composer to create custom music. I recognize that working with a music library is also a viable option for many creatives – that is a somewhat different process.

From the beginning of the project, it’s my job to open a clear line of communication about what exactly we all want for the music, to determine who the final decision makers are, and to figure out a way to keep things on track.

In the beginning, it’s often helpful to get very granular details by sharing existing examples and quick, messy custom prototypes to really hone in on the right direction. Many projects move fast, and sometimes projects change in the middle, so getting that communication going is important for any tweaks or adjustments that we decide on to get the music working well, as fast as possible.

Once in awhile during the review process, I’ll get feedback such as “It’s not working” or “I don’t like it.” That’s clearly not enough feedback. If that’s all I get, I have to do my best to draw my client out more. I don’t need them to tell me their hopes, fears and dreams, but I do need to figure out what music is going to work, so I don’t throw out the good parts and then I need to figure out what isn’t working with the music, so I can fix it.

Very often my job is to translate emotional terms, narrative structure and thematic elements into music.

Here are 5 recommendations for communicating with a composer:

- Use descriptive language. It’s helpful to use emotional words, and try to tie them in to thematic elements in your project. It’s great to use the language that originally inspired you in the creation of your masterpiece. These ideas can be foundational for the music as well. For instance, if you need the music to build right after the sunrise, or if you need the music to pause when the main character looks away because she’s remembering how much she misses her first pet Sparkles… those are the elements to concentrate on and to communicate about. Sometimes you need the music to track a character’s mood, or you need the music to play against what’s happening on the screen.

- Be careful of using musical terms. Musical terms generally have very precise meanings, and if not used correctly, they can be confusing to your composer and muddy up your intention and in turn, your music track. I’ve been in situations where a creative person recommends that they want something raised up an octave, but they really mean just a higher key – or that they want something slower, but they actually mean in a minor key. No worries. It’s my job to translate, so if you’re not sure, it’s OK to say that you’re not sure, we’ll figure it out together.

- Try to have specific existing music examples. If my client doesn’t provide examples at the beginning of the project, I frequently put together a quick playlist that we review together. These examples allow us to begin a conversation about genre, instrumentation, tempo, and feel and anything else that might be relevant to the project – and since we’re listening to the same examples, we can generally get the majority of the information that I need to create an audio brief it one doesn’t already exist, and can begin composing. This process is also a great way to begin our clear line of communication.

- Be prepared to provide data. No matter what you’re working on, you’ve already worked on it longer than the composer you’re bringing in. You likely have some valuable insights to convey about audience, target markets and your competition or industry. If it’s a commercial, you might have some analytics that you’ve rolled into your process already. If you’re working on TV show or film, you might either have some focus group data or at least some anecdotal ideas that you are drawing from. Your composer doesn’t necessarily need raw data, but giving them a brief summary of this information can be a key insight into why you’re making some of the choices you’re making about music. This data may also inform some of the decisions the composer makes in one direction or another.

- Be open. As in any creative process, you may ask for something and realize that once it’s compiled, you don’t like it. No worries! Pairing music to picture is an iterative process. I find it helpful to figure out what is and isn’t working and to move quickly forward from that information. It can be helpful in these situations to focus on the outcome, not necessarily the process. If you’re focusing on narrative, subject matter and how you want a scene to be conveyed, chances are that you’re going to be in the ballpark of finding the right music. And sometimes even small tweaks can make all the difference between what isn’t working too well, and what’s totally working.

Pairing music with video is an exciting process. If you have the chance to collaborate with a composer who is a willing partner and good listener, then there is a high likelihood that the composer will take great care with your project – the same amount of great care that you have taken to get it this far.

I received feedback from a longtime client a few years ago. Every week, when I sent over my full orchestrations and the final mixes of my music synced to picture to the audio director, this was usually cause for a small crowd of people who worked on this project to gather around the audio director’s mixing console and watch it, some watching the whole project for the first time. It was only then, and only once the music was synced that the project felt finished. That, to me, is how I know when we have the right music.

Good luck, and let me know how your experience with of communicating with a composer goes!

Jerome Rossen is a composer, songwriter, producer and professional musician. For 18, Jerome has created music for advertising, apps, and kid’s video games. Jerome has placed his music in major TV shows like “The Bachelor” on ABC and MTV’s “The Challenge”. Jerome also creates the music for the Happy Tree Friends, a very funny (though very violent) cartoon for adults and mature kids, with a huge cult following. He runs Freshmade Music, an independent audio studio. You can learn more at www.freshmademusic.com.

Seven Steps of Creativity

Creativity can seem elusive. For some people, it’s loaded with fear and superstition. The fear is that just by asking, trying to look the muse directly in the eye, we risk scaring the muse away!

With a little bit of faith in my heart and my fingers firmly crossed, I took some time to examine my creative process. I was somewhat surprised to learn that I go through a similar process each time I complete something creative. In my examination, I broke my creative process down into steps. Here are:

My 7 Steps of Creativity are: the spark, organization, the brainstorm, assessment, execution, revisions, declaring it done.

I realize that there are likely tons of really great ways to approach creativity effectively and there is probably no real magic to the way I personally approach creativity. This just happens to be mine.

I notice that I don’t always use each of these steps in order — sometimes I skip around a little bit, but I do touch on each one at some point. I’ve outlined a brief explanation of each of the 7 Steps below and I’m including some tips on how I try to optimize each one.

How can you use these steps and how can they benefit you? For me, I use this process for writing articles, producing music tracks, writing songs, and collaborating with other creative folks. This process may be helpful for you if you’re working on a large project that you need to tackle but seems daunting, or if you’re trying to figure out the best way to start a project — perhaps you’ve got a temporary case of writer’s block ? And why don’t we just assume that all writer’s block is temporary?

1. The Spark

The Spark is that kernel of an idea that seems to magically enter into your head. Sometimes the spark comes quickly, in the shower or when you’re driving — hopefully not when you’re trying to do both! But sometimes you have to will it into existence. Either way, you want to be ready when your great inspiration arrives. Here’s what I recommend:

Optimize Tip: Create your space

The idea here is that you want to open the creative space in your mind for the spark to come. A free mind is an inviting environment for creative ideas.

Do whatever you need to do, both mentally and physically to make sure your mind is free of distractions. When I have a lingering bill, phone call or email to write, then I take care of it, especially if it means it will free up more room in my brain to be creative. I can be easily distracted from checking my email and checking into social media, so I create some guidelines for myself.

I don’t like to begin work until I have an organized work space. If it would help you to have a clean work area, then set aside some time or put an action plan together about how and when you’re going to clean your space. And if you have to, find somewhere else to work, like your local coffee shop.

A note of caution here — if you find that the “create your space” step is taking more time than you expected (“Oh, my 5th grade class photo… I wonder where Desmond is?”) than be careful that you’re not using this as a reason to procrastinate.

2. Organization

When I was just starting out composing music for film and TV, I would have a tendency to jump the gun and start making stuff way too early in the process — right after getting the spark — without having nearly enough information. I would make a number of assumptions and then be prepared to deliver music based on these assumptions to my clients. As you might imagine, many of my assumptions would be wrong, my music wouldn’t be quite right, and in the very beginning, my ego was a bit bruised. If I had been a little more patient and just asked questions and listened to the answers, I would have been in a much better position.

Optimize Tip: Gather information by research or listening

Answer who, what, where and when. This is when you’re the project manager; where you identify what you’re doing, how you’re going to do it, who’s responsible for what, what your deadlines are and whether there are any additional resources that you’re going to need. If you’re working with clients, this is the part where you listen to how they understand the project, you ask lots of questions, and you clarify whatever you need to. For many creative projects, it’s often clear in somebody’s head what creative solution will work — if you’re working for that creative person, you want to make sure you get the full creative download on what they’re expecting, so it becomes clear in your head too.

While capturing all of these details may sound stifling, most creative folks thrive on having a structure so they know exactly what they’re working on. I personally love knowing what my deadline is, who my target audience is, who I’m working with, who will be reviewing my work, and what the parameters are for the project.

3. The Brainstorm

The point of the brainstorm section is to get lots of ideas together so that you can choose the best ones. Sometimes my first idea is good, but I’ve noticed that I can push myself to see “What else can I do?” or “How else can I solve this?” In situations where I’ve come up with multiple ideas, I’ve often taken elements from a few different ideas to find the winning solution.

Optimize Tip: Allow yourself to create without judgement

Sometimes when I’m writing a piece of music, I may write three really quick sketches knowing that I’ll assess them at a later time, and honestly not really worry about whether they’re good. This is the time for creating content, not judging it. It’s critical in this stage to turn your editor off so that you can freely express your ideas without the little voice inside you constantly saying “no, that sucks” or “people are never going to like this.”

4. Assessment

This is when you can let the editor in and freely judge the brainstormed ideas. For me, I really appreciate starting the assessment process after I’ve had some space from the initial brainstorming session, whether it’s overnight or after I’ve taken a brief break from creating. This way, I can try to have a fresh perspective, and I can try not to be emotionally attached to any one idea.

Quick note — while the assessment step may take place here, and it may take place again, later in the process.

Optimize Tip: Try to be your own fair, balanced critic

The sooner you can be honest with yourself, the better. If you really like something you’ve created, and you’ve gotten positive feedback from folks who understand what you’re doing, there’s a good chance that some group of folks out in the world will like it too. But if I create something, look at it a few days later, and I’m not in love with it? I give myself permission to to step away and start again, especially if I don’t know how to make changes so that I’ll love it. Sometimes the quicker that you can judge that something won’t work can save valuable creative time to focus on the ideas that you think are worth pursuing. Besides, I always keep all my work — even the discarded ideas because sometime those so-so ideas get revised and turn into great projects.

5. Execution

Optimize Tip: Create fast and cheap prototypes

You want some way to be able to really quickly assess the viability of your idea. Sometimes you can only see a dramatic flaw from a mockup that you can’t see on paper. I record demos and listen. I audition instruments and see how they’re working together. If it’s appropriate, I get feedback from trusted sources. Again, it’s often helpful to allow yourself to experiment, fail and revise in this step.

Optimize Tip: Try 3–5 versions

Put together 5 beginnings. Create 3 endings — quickly, but don’t polish them yet. You want to put only enough energy in to see whether your project is working. If it isn’t, create some more. If it is, and all it needs is polish, then that’s fantastic!

(At this point, I often go back to #4 Assessment)

6. Revisions

If you have an inkling in your gut that you should change a small part of your project, do it and see if you like it better. In the majority of these situations, a small change might take a little more time to fix, but is totally worth it in the end.

Optimize Tip: Revisions can make or break the project

Sometimes it’s easy to blast through the initial creation phase of a project, but I notice that I slow down for the analysis portion. I often find that analyzing projects to figure out how to improve them can take much more time, and can be a much more delicate process. Very often a few very small changes can make a big difference in a project. When I’m working on a music track, I try to listen to reference tracks to make sure I’m getting the mix that I’m trying for. During the brainstorming and execution steps, I may make broad strokes. In this revision step I’m more conscious of working carefully and more skillfully.

7. Completion — Declare it Done

Sometimes you have an external deadline when you have to turn in your work, so that whatever you’re working on can go to the next step. And sometimes, creatively you need a break — you’d like to wrap it up and start something else.

Optimize Tip: Try to get it finished “enough”

There are times when I’ve finished a project because I’ve run out of time. In fact this can sometimes be a blessing. There are projects that come together very quickly — 90% is finished in a day or two, then I take 3 days to try to polish the last 10% (See the Revisions Step above). Be careful with how long you take to complete the final polish. When you think a project might be done — get some feedback if you need to, take a deep breath, do one last check, then pitch it, send it, ship it — whatever needs to happen. Then move on to the next project (and perhaps start again at step #1!).

Creating something can be a pretty messy process. In my mind, I come up with an idea, work on it, then it’s finished. But when I stopped to examine my process, I realized there is a lot more to it. I also realized that I don’t generally bring superstition and fear into my creative process when I’m mindful of following the 7 Steps of Creativity.

If you have any interesting tips to share about your creative process, or if you have any questions or feedback about these 7 Steps, I’d love to hear from you. I’m always fascinated to learn about how other folks approach their creative process. I’m especially interested to see how other folks start and finish creative projects. Go make stuff!

Jerome Rossen is a composer, songwriter, producer and professional musician. For 15 years, Jerome has created music for advertising, apps, and kid’s video games. Jerome has placed his music in major TV shows on NBC. ABC and Fox. Jerome also creates the music for the Happy Tree Friends, a very funny (though very violent) cartoon for adults and mature kids, with a huge cult following. He runs Freshmade Music, an independent audio studio. You can learn more at www.freshmademusic.com.

My Job’s Most Important Skill

The most important skill in my job is listening, though perhaps not the way you may be thinking if you know me. I run an independent audio production studio called Freshmade Music, so I rely on my ears for my job. What I’m referring to here is listening to what other humans are saying. I’m talking about communication; really understanding what my clients and potential clients are looking for, where we can bounce ideas back and forth so that not only do I understand what they’re saying – and here’s the kicker – they trust me. Because if you’re in a business relationship of any kind, and you’re really listening and understanding what your role is, and you’re able to deliver and excel effectively in your role, you begin to gain trust. This is especially important fast-paced environments, like the industries I work on, when I’m creating music for advertising, apps, games and TV.

I’ll explain more. But first we have to talk about burritos. My daughter really likes burritos, so we order them to-go from her favorite taqueria once a week. She really likes what she likes, but she really doesn’t like what she doesn’t like. Who doesn’t? I don’t blame her. When she wasn’t really old enough to place her own order, I’d order for her. Sometimes I would place our order too quickly while trying to keep the rest of my family’s order together in my head and screw up her order. I’d either forget to specify which kind of beans she wanted, or forget to tell the restaurant that she wanted the regular size, not the smaller kids size, because she likes to eat half today and save the other half for another meal. How would the taqueria know that? They wouldn’t! There were times when she got the wrong order, and she would get upset. Mean Daddy. (As I said, it was my fault – at least like 90% of the time). Where was the error? Was this a bad burrito? No. Was this suddenly a bad restaurant? No. This was quite simply a communication breakdown. I didn’t stop and take the appropriate amount of time that I needed to place the order correctly, thus she didn’t receive what she wanted.

Here’s another example, this one from my work experience. When I was just starting out, a client explained the germ of an idea to me. At this early point, I was so excited! I immediately committed my first error when I assumed that the most important thing I could do was to prove to them that I could read their mind and show them how great my music was. Good intention, but wrong decision. What I didn’t understand in this early project, is that I failed to slow down and take in enough information to even begin producing music that the client might like. I should have asked more questions about genre, music function, target audience, instrumentation, and more. This in turn would have sparked a more in-depth conversation with my client. But no, I just started creating music that I thought was perfect, and thought that the client would just love it. Well… that early experience was eye-opening. I couldn’t believe that my client didn’t like the cool music I put together! But I quickly realized, the music was fine; it just wasn’t the right music. More importantly, I hadn’t taken time to communicate with my client, so we weren’t really collaborating yet. I didn’t have any buy-in.

It took me a few more projects to realize that if you have full buy-in from them team you’re working with, especially in a creative industry like mine, you’re much more likely to stay on the team for more iterations and to see the project through to its end. Luckily my client was patient and stuck with me. My first draft wasn’t for naught – this track led to a very productive conversation with the client and she allowed me to submit more music that was much closer to what we both thought would work, and after a few tweaks my final music was approved.

Do you have any tips or experiences you’d like to share? Please share them with me at info@freshmademusic.com.

Jerome Rossen is a composer, songwriter, producer and professional musician. For 15 years, Jerome has created music for advertising, apps, kid’s video games and has placed his music in major TV shows like Gordon Ramsey’s “The F-Word” and “The Bachelor”. Jerome also creates the music for the Happy Tree Friends, a very funny (though very violent) cartoon for adults and mature kids, with a huge cult following. He runs Freshmade Music, an independent audio studio. You can learn more at www.freshmademusic.com.